Built in Shenzhen

Reflections on China, Part 2

This is a follow-up post to Landing in Shanghai. Thanks to Savannah for draft edits.

While in Shanghai, I was told a few times Shenzhen is a planned city: car-centric, not walkable at all, completely unlike Shanghai’s dense interconnected streets. I was picturing, and somewhat bracing for an industrial city; pedestrian-unfriendly and unappealing. Shanghai was cold, so I was also expecting cold in Shenzhen as well, forgetting about the difference 2.5 hours south by plane can make.

Stepping out of the airport in Shenzhen (a massive airport in its own right) I instantly felt a different biome welcome me: warmer, a bit more humid, and sunny! Whereas Shanghai was frosty and overcast, Shenzhen was just possibly shorts-weather (I would still get more flak for my half-pants later). We made our way to our taxis to be taken to the hotel.

There were indeed lots of cars, lots of roads, and lots of traffic (a staggering percentage of it electric, but traffic no less). What surprised me was all the green: driving to the hotel I saw trees with lush broad leaves, happy plants everywhere, and even vines hanging off of branches. Perhaps it was coming from Colorado in January where everything is some shade of brown, gray, and dull winter green but this was a breath of fresh air, sorely needed.

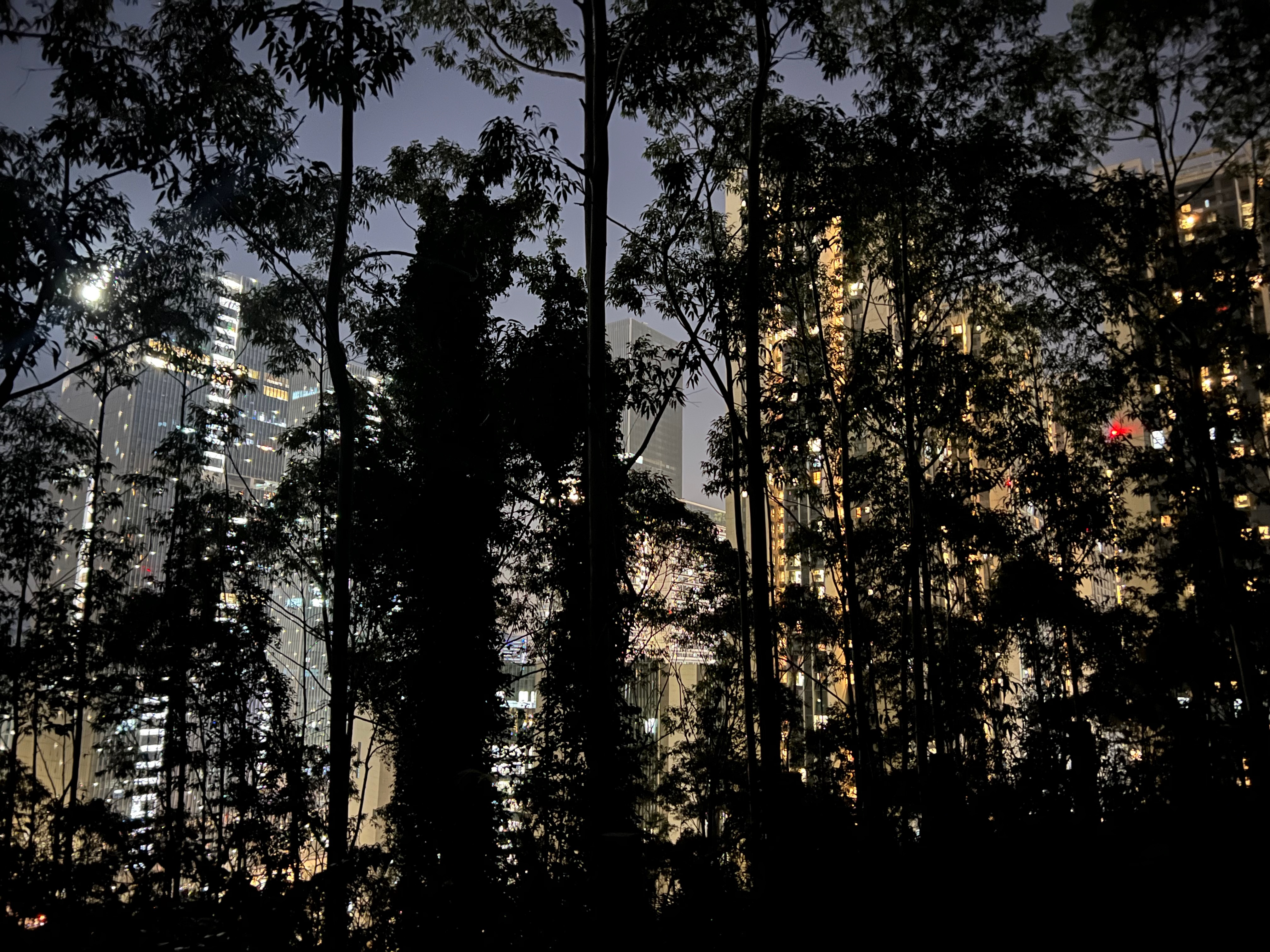

I wandered through some amazing parks spread throughout the city- parks which didn’t feel overly-designed or manicured with plenty of desire paths splitting away from the main paved paths. Some parks are built right into a valley or on top of a large hill - meaning you could really work up a sweat crossing one of these and almost forget you are in a city. That is - until you see a massive building peeking through between the brush.

It’s hard to describe how delighted I was with this: during my 10 days in Shenzhen I was immersed in technology, constantly meeting new people and having great conversations, often in buildings far away from the sun. It was a gift to be able to leave all of this and walk in the trees alone; often listening to an audiobook or nothing at all.

At times it was hard to tell where a park stopped and the rest of the city began. Combined with the ability to walk to a clean, functioning subway, the proportion of electric vehicles riding around on the streets, the relative safety I felt at at all times; there were glimmers of a future I see portrayed in Star Trek; leaves and trees gracefully mixing with glass and steel.

I explored some of these parks at night, and that’s when I noticed how the parks explored me back. It was inside one of these parks at night by myself that I realized I wasn’t alone - I was accompanied by dozens and dozens of cameras, each with a subtle red light glowing through the leaves. I made it to the top of the hill (about a 30 minute walk), sat down on the bench in the darkness; with only the cameras for company.

It was a fascinating confluence of feelings: the serenity of the tall trees, far up above the hustle and bustle of the streets below. Yet still feeling quite small looking up at the massive, light-covered towers. Physically alone, but having my every step logged and monitored - by humans? by AI? the glowing red lights winking at me through the leaves, no step or turn of my trail unaccounted for.

how stuff is made

One of the highlights of the trip was when Scalable HCI graciously set up tours in live factories, complete with guides answering questions and busses moving us around like a middle school field trip. Everyone chose a seat buddy and we got to know each other over the 30+ minute rides between stops. The factories themselves were in relatively nondescript industrial districts that weren’t too far from residential or commercial zones: it was all kinda folded in next to each other.

The first factory was a site where they made plastic parts with injection molding, assembled PCB boards, and other fancy stuff beyond my understanding. The second was actually located one building over and manufactured injection molds for anyone who needed them - including the first factory. Imagine a grungy machine shop, dozens of CNC lathes running simultaneously, loud, grimy windows and concrete floors, and no masks or safety goggles to be seen. I blew some stuff out of my nose that night, probably some combination of oil smoke and who knows what else.

I’m not sure whether these workers have enough agency to simply not care about safety equipment, the company is too lax to enforce it, their margins aren’t enough to justify caring, that’s where the state of regulation is, or some combination of all of these. It’s a far cry from what the working conditions I’m used to in the U.S. look like and explain some of the economic realities that make building so much in China feasible.

Our final stop was the Seeed Studio factory & warehouse, a company I have gladly ordered from before. This warehouse is where they assemble, test, and ship a huge range of products. They even had a wind tunnel for calibrating weather sensors! I found Seeed’s warehouse to be much closer to what I would expect to see in the States: everyone in a uniform, caution tape around doors that swing open, masks and ventilation, and a considerable number of windows open to let the cool breeze in.

Some more reflections on the factories:

- there was simultaneously more and less automation than I expected. sometimes a machine was absolutely sending it and spitting out dozens of pieces of something per minute. but at the end of the conveyer belt, a person would be picking up the things one-by-one, putting them under a digital camera, and verifying the part was printed correctly.

- In the age of automation, AI, and everyone yelling about the coming economic collapse it’s interesting to see how involved humans are in the creation of stuff which doesn’t live on a screen

- sunlight is not good for electrical components so it’s not good inside factories either: UV and temperature fluctuations should be avoided. this made some of the working environments pretty rough (completely indoors, enclosed, fluorescent lighting) but parts of the factory that didn’t deal with sensitive parts had more comfortable environments

- quite a few of Seeed Studio’s raw components come from elsewhere in Shenzhen: the whole city is supplying itself, in some sense becoming one giant node on the map that raw material flow into, and products come out of.

- This is the magic of Shenzhen that people refer to: shipping times are measured in minutes to days instead of weeks to months, allowing near-realtime prototyping and in person communication with your suppliers.

- MOQ (minimum order quantity) is everything: it’s the minimum number of individual units a factory will consider making for you, usually a factor of sustainability for them, making overhead logistics worth it, or upfront costs on their side like machining one injection mold.

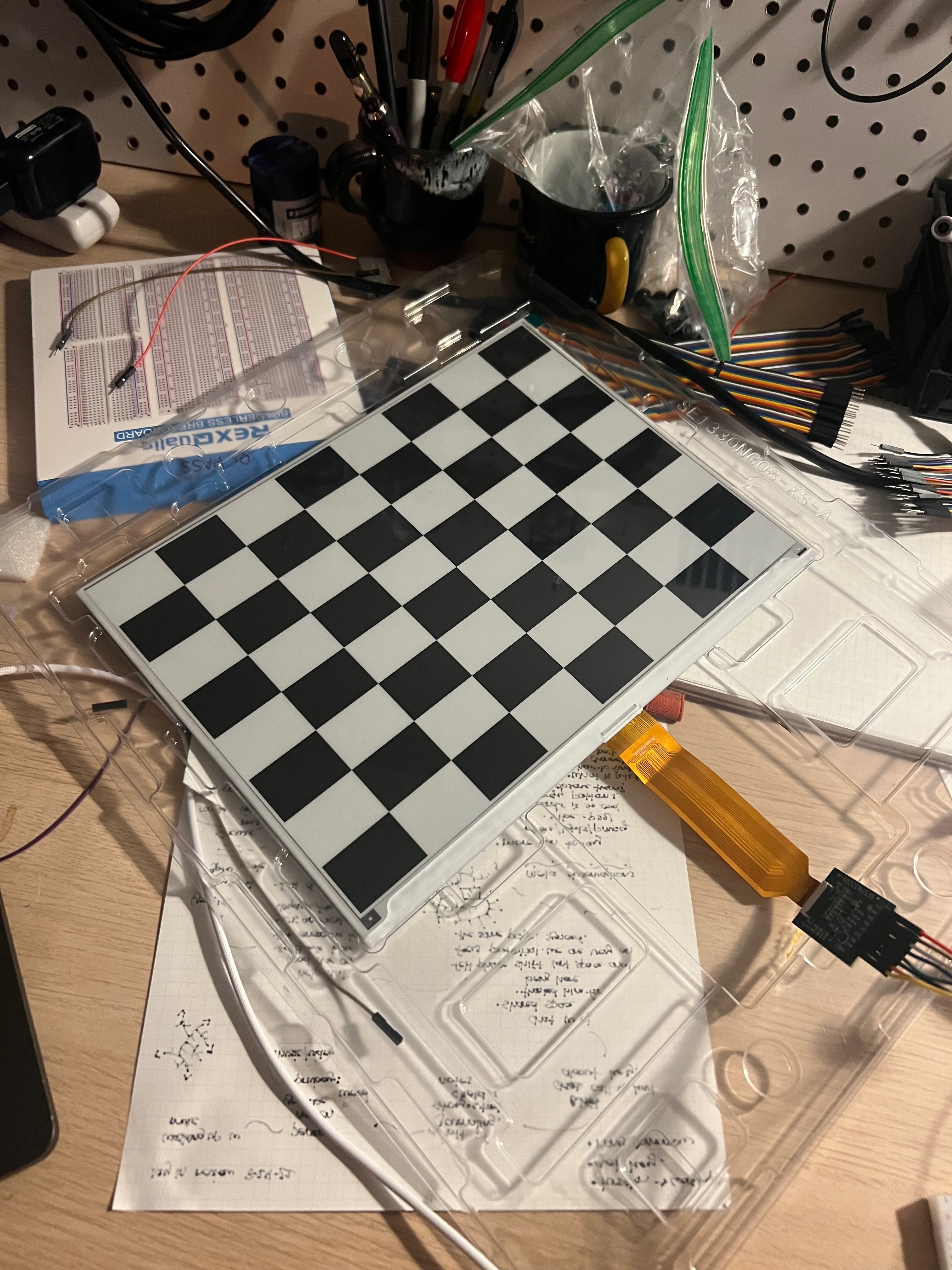

- This number is often in the hundreds or thousands, but I did order epaper displays from a factory with an MoQ of 1 which surprised me. Another eink panel I got though has an MoQ of 500, whereas the controller chip for it had an MoQ of 3,000.

- inventory management is constrained by space and people: the raw materials come in by truck. You gotta unpack them, piling up the useful stuff somewhere and the rest of the packaging material somewhere else. Then you inspect the raw material, possibly prepare it or process it in some way. Then you clear out the machine, load material into there. The machine makes the raw material into something. Some things are too delicate to just pile up in a giant bucket. Someone needs to take a look at the thing that came out, maybe measure or examine or even test it, then put it into an organized pile. Someone else then puts that pile into a package of some sort, puts a nice label on it. And then they need to be piled up for the delivery service to come and take it away.

how stuff is bought & sold (at Huaqiangbei) #

Huaqiangbei is a neighborhood/district of Shenzhen that offers many factories of Shenzhen & beyond to 1) make their presence on the map known 2) supply physical samples and small quantity sales 3) negotiate bigger orders. There are of course websites for factories, and having a friend of a friend introduce you is ideal. But if you’re someone trying to find something in Shenzhen and starting from zero, this is a fantastic place to start.

It’s hard to convey the scale of HQB: According to Wikipedia, there were 38,000 businesses in the district in 2020. You can absolutely get lost and disoriented in there. Buildings are often connected to each other at multiple levels. Stalls are not always organized in rows or columns, sometimes they snake around with the numbering system following the path rather than sticking to any grid. There is a certain illegibility to the place that becomes your responsibility to wade through and figure out, bring a friend to split the cognitive load, or hire someone to help.

Scalable HCI was organized us first-timers into groups and I had Andy leading our group who’d been there a number of times before. He polled for what we were all interested in seeing and then charted a course into the chaos to try and roughly aim our group at those things, as well as stopping by a couple personal favorite stores to show us the joy of an entire store specializing in small electronics repair kits and soldering supplies.

Any map of Huaqiangbei will likely be out of date the day it’s made. It’s not an exact organization system. For example: there are several buildings for phones. And there’s a separate giant building for cameras. But the camera section has some phones in it with notable cameras. And of course there is a third section dedicated to refurbished Apple iPhones. And each of these might be a 5 or 10 minute walk apart.

To find something specific, you’re going to be running around a bit. There are signs, but they’re usually questionably translated (if at all) and often so generic as to not be useful. The highest rate of return is finding a similar-enough class of thing to what you’re searching for, bringing a couple photos along, and asking via Google Translate if the people at a stall have this item, or know someone else who does.

Some of these booths were lively and had people constantly stopping by. These were generally closer to the ground floor or the entrances to these buildings. The booths further away, on higher floors, had a different situation: I saw people sleeping in their booths or in one case, a 7 year old kid manning the booth while playing video games. It made me wonder about the economics and perhaps social pressure of having someone present at your booth, even if to get any information or prices at all they need to dial someone else to answer your question.

I gave myself a quest: I wanted to find a nice e-ink panel (the same kind the Kindle has for a screen, but bigger). During my first day of wandering around I saw more Dyson hairdryer knockoffs than I could shake a stick at, capacitors and LEDs of every size, batteries, control knobs, cell phone jammers that would get me put into a small jail cell at a US airport, USB chargers, solar panels, and pretty much anything else that moves electricity through it. It was awesome and overwhelming. But no e-ink screen. It would take me another visit to find the supplier, and another visit still to pick it up a few days later.

the haul #

During my four visits to HQB, I acquired a couple 1.69 inch ePaper displays (straight from the factory!), a small solar panel, a pocket multimeter 🤓, a USB power tester that says “please look forward to this feature’ when I switch it to English, and various other fun knick knacks. But the prize of my trip was a 13.3 inch eink panel, also straight from a different factory that manufactures them! More on this project soon.

building my own stuff #

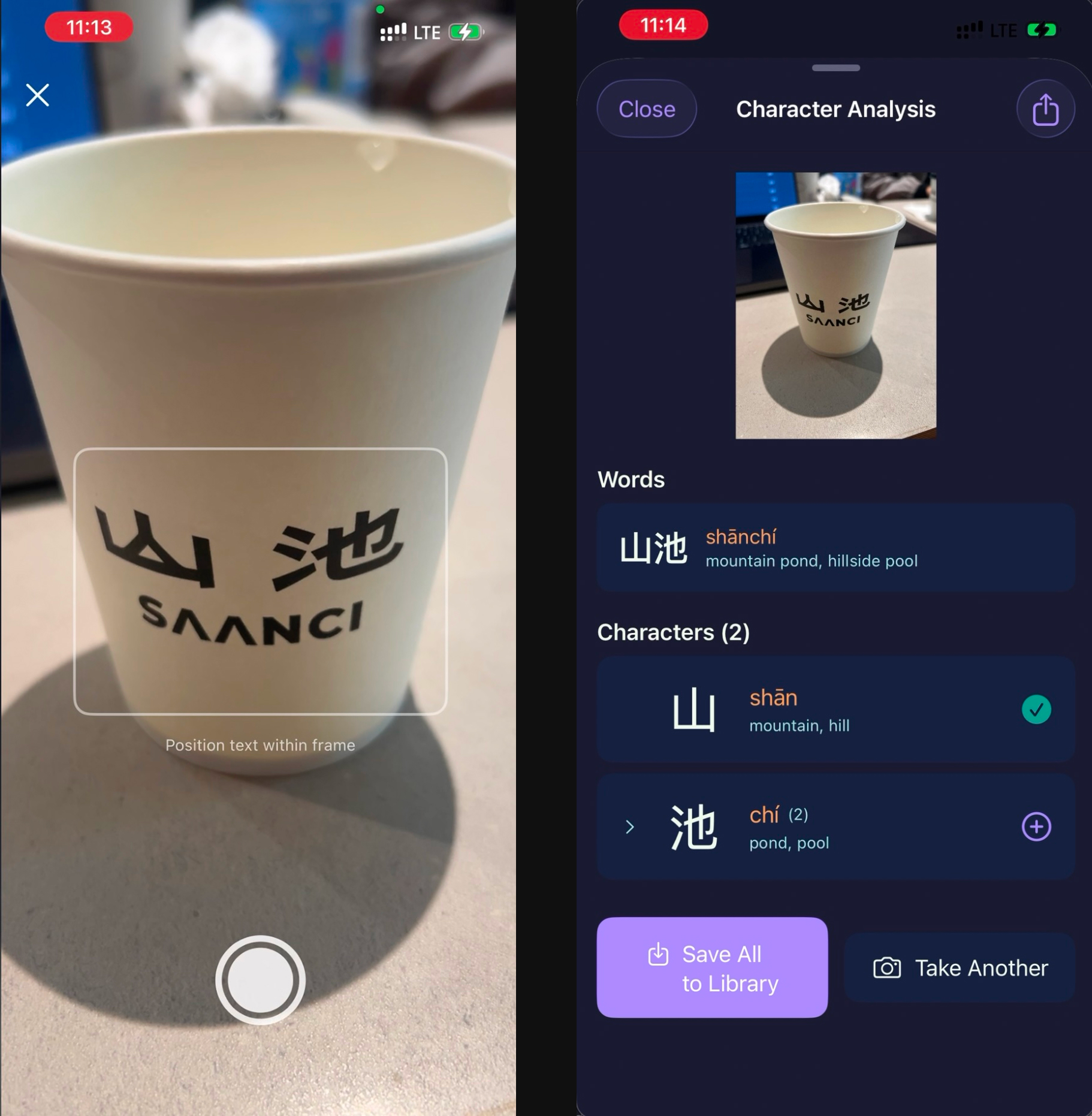

At some point during the trip, the combination of overwhelm from seeing everything in Chinese yet understanding nothing, along with agency rubbing off on me like second hand smoke coalesced into an evening of building with Claude Code. Out popped CharacterCollector; an app to help me understand and learn a little bit of the language I was surrounded by.

It had a photo capture mode, and then the photo would get analyzed by Claude Opus to generate this sheet:

It lets me add these characters as flashcards, review them, and see a gallery of all the photos I took. This was my HCI (human-computer interaction) project for my week there: a way for my phone to help me better understand and exist in the world, conforming to the way I think rather than imposing what someone on the opposite side of the planet decided was a good translation interface. It’s small, entirely vibe-coded, and it was a glimmer of a future where tools are more bespoke; designed for the context of where I am.

takeaways and ponderings

China, but specifically Shenzhen for the sort of things I’m concerned with, is a place where things get built. There are economic and regulatory realities that make that possible, as depressing as some of them are; and there are cultural realities that also make that possible; inspiring as it is to see so much solid engineering and a willingness to relentlessly figure out the problem at hand.

It left me wondering what we have given up in the States by outsourcing so much of the ability to produce things. In Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, Dan Wang describes the past four decades of the United States becoming a “lawyerly society” and China an “engineering society”. To the extent of what I saw in China and what I know and experience at home: I believe that assessment to be valid. Dan continues on to say that neither approach is without faults: both countries have more to learn from each other than to disagree on when it comes to balancing regulation and creation.

So that’s the situation. I don’t think it can easily be changed by the US threatening tariffs, nor do I think China wants to give up the trade that is injecting capital and demand into their economy. However I do believe there has been a decreasing amount of slack in the system (whatever scale we want to name that system) - Covid showed us what happens when the system gets shocked: shelves go empty and institutions have seizures. On the grand scale of things, that was pretty minor compared to what we might experience with a large scale energy grid disruption or even a single nuke.

What does the world look like when AI does for physical engineering what it’s already doing for software engineering? How soon will that be, and who will stand to benefit the most? In a world where anything can be built easier and cheaper and faster than ever before, what do we put our attention towards building? How do we build things that add to our resilience rather than adding yet more complexity and reliance on other countries’ energy supplies and supply chains?

I believe there are some answers to be found in both countries; neither has it fully right. I’m grateful to be able to visit China and get a sense of an alternate reality. Not one I would trade mine for; but one where some of the base parameters of the system are different enough that I get to feel into the vaster possibility space that surely must exist for both countries and the people in them.

On a personal level, my visit to Shenzhen has left me with the feeling that I can and should create more things. Sure, I won’t be manufacturing microchips in my garage. But building something myself means I get to choose more of the values and tradeoffs that go into its creation, and perhaps more importantly, I’m going to know how to repair it or help a friend make one, too.

Thanks for reading <3